Housing Affordability and Availability remains a fraught topic about town these days. On the Supply side, it is well known at this point that we need thousands more housing units, and that each year the deficit of housing grows. We are not keeping up to current demand, let alone making a dent in the existing shortages.

Understanding a bit about the basics of economics and business cases for new housing supply might go a long way to understanding what is going on. When people hear of $300,000 for a micro suite, they react thinking its nuts. However when you dig a bit deeper, you find out that the rules that we have which guide development in our country basically mandate this situation - combined with modern work standards in both material supply and construction wages being strong (it's own supply/demand situation as well).

This article is about new housing supply, building and developing it, not about the price of existing housing. Also of note - while housing prices may be coming down, that does not change the number of folks who are unable to access correctly sized housing - like families to family housing, and young people/students/empty nesters to suitably sized and situated dwellings. New housing construction will continue to be required regardless of what housing prices do - even just to replace housing that is nearing the end of its life.

Yes interest rates, mortgage policies, and demographic changes all have large parts to play in the demand side of the question; we are going to deal specifically with the supply side in this article. Also, the relative buying power of money informs the "cost" but also informs it in context with what folks are earning. If housing costs were to drop dramatically, a person could reasonably surmise that so too would the earning of average employment and the quality of the work, meaning the change in affordability relative to income could be a wash. When we have folks living in RVs in peoples back yards, and 10 people in a 3 bedroom single family home (Chapter 6), we need to do something about the supply side.

The premise of this article is thus: unless you are able to afford what we collectively currently decree as the "minimum" quality of housing, regardless of if it suits your needs, desires, culture or lifestyle - you simply will not be allowed to afford to rent or own a place to live unless the government pays for it on your behalf.

There is three major factors which create the minimum price you pay for a NEW house:

- Land Cost

- Construction Costs

- Parking/Shared Amenity/Landscaping Costs

LAND COST

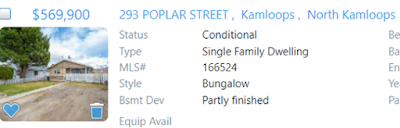

This is what the lot you are looking at to build a new house/duplex/apartment building costs - that is the land cost. For example:

293 Poplar Street - $569,900. If this were to be torn down, and rebuilt as a new house, the cost of the lot is $569,000. So after that, all the construction costs will be on top of that. If you build two units, a duplex, the land cost per side is $569,900 / 2 = $284,500. In some of the few places that bare lots are still available in Kamloops, Juniper Ridge for example, those bare lots are selling for about $400,000. Bare land has the benefit of being undeveloped, lowering some costs like demolition of an existing building, but has costs of its own, site prep, retaining walls and utility connections for example. Inside the cost of that lot is new roads, sewers, water, street lights, hydro, gas, which all go into the cost of the lot. And those lots in Kamloops are very rare, and increasingly very expensive.

Importantly, you can see that in Kamloops, the land cost is the primary driver of the selling price of homes and lots - it does not matter much about the house or lack thereof on top. The same has been happening in Vancouver for 30 years. When land drives the cost rather than the improvement, that raises the floor on housing prices dramatically.

In any case; the cost of the land, using the lot on Poplar listing above as a base, divided by the number of units give you a base cost per unit -a "door cost", and that gives you a curve that looks like the following:

With each unit the land cost gets cheaper. So the more density you add, the cheaper each subsequent unit can be. This is pretty straight forward. What is complicated, is that in Kamloops, 94% of Residential Land only allows a maximum of 1 or 2 units. So our zoning code mandates that we are only allowed to divide the cost of land by 2 (just 1 in most)- avoiding the further savings that say 4-10+ units might make.

This is regulated by what is called Zoning. These are municipal laws designed to address where housing, commercial, industrials (uses) etc. go, and at what density. They are led in part by Infrastructure (roads, pipes, sewers, power), as well by Politics (Official Community Plans, City Council votes, City Staff priorities, grants). They are different for every community, city, every province, every state and every country. They are different not just in what they prescribe, but in how they prescribe them.

Zoning has nothing to do with safety, or building "safe, sound" homes. When people want to change regulation on zoning, they are NOT endangering the lives and safety of future occupants.

For examples on how and what can be different about zoning City to City and area to area:

some cities do not regulate density, only floor-area ratio or height. Other places regulate density but not size. Some places focus on form, character, architecture (like Sun Peaks and Whistler) while others focus on public amenity contributions (pioneered in Vancouver). Every single place is different.

There is no one size fits all - this indicates that there is nothing inherently correct about any particular zoning regime. Unlike Structural Engineering, the tensile strength of a bridge deck designed to carry a certain load, or the snow load of a roof - where one thing is correct and one thing is not - zoning has no true correctness. Its metrics are arbitrary, and the results are not quantitative or qualitative.

It can however make an area poor, or rich - it can exclude certain things or people or ways of living. Once again see

Chapter 6. Inappropriate zoning can lead to overcrowding and slumming as can bee seen around most Canadian Universities - in the name of preserving lower density for "character", many universities have 'student slums' surrounding them with people living in very cramped quarters not designed for dense habitation because alterative housing arrangements are not made legal by zoning. I have argued in the past that zoning has created and enforced the systems that make reinvestment, revitalization and vibrancy so hard on the North Shore as well.

|

this zoning in Sun Peaks focuses heavily on congruent architecture rather than density, modelled to look like Innsbruck, Austria, below:

|

New York, uses Air Rights based zoning to provide dual incentives for density and heritage preservation all at once - though the effectiveness of that and the resulting

Billionaires Row projects have perhaps not delivered the results hoped for - this underlines the point that our bureaucratic zoning tools in even the most cosmopolitan of cities are not always producing the results they were intended to.

Changing zoning to allow more density can allow housing to be less expensive by lowering the amount you pay for a Sq. Ft. of land - and it can also have knock on effects in lowering the cost of servicing for the City, and thereby lowering taxes (

Chapter 1). Further it can grow the local economy making local businesses more competitive (

Chapter 2). One of the greatest effects can actually be the 'un-slumming' - the process of reducing overcrowding by actually providing closer to the number of units and types of units required for the demographics of people who need or want to live in a specific locale. Lastly, changing zoning can provide for investment in chronically disinvested areas, fix potholes, improve parks and street lighting, and create climate mitigation infrastructure, for flood or other events (

Chapter 3).

CONSTRUCTION COSTS

Construction Costs are the price it takes to build the building itself: Put up the walls, get the permits, the engineers, put on a roof, make it water proof, heat it, provide water and sewer, landscaping etc.

Most of these costs are regulated by Building Code. Technically it is within a Cities rights to have their own building code, as Vancouver does, but most follow the provincial BC Building Code which itself is informed by the Canadian Building Code.

Most of Building Code is about building safety or occupant health (fire escapes, structural considerations, ventilation, wiring standards, sewer capacity etc). How many 2x4s in a wall? How many screws per foot? Mistakes are sometimes made (see leaky condos).

Many aspects of building code are comfort related - for example the minimum number of toilets required, or minimum amount of lighting, minimum amount of plug points in a room, or minimum ceiling height.

Some are also about (or supposed to be about) accessibility for differently abled people. Maximum steepness of a ramp, widths of doors, heights of door knobs or railings, size and number of elevators.

And many are also political - enforcing the use of one material or system over another because of political trends in climate science, or local manufacturing the government wants to incentivize. (see EV policies)

Building Code is The Bare Minimum that is allowed to be built. Building Code in many ways is informed by safety - we don't want light fixtures installed that are likely to explode, or fail to provide a means of escape in a time of emergency.

Building Code becomes far more stringent as the size and the complexity of a building increases. A 20 story tower with elevators, fire suppression, huge HVAC systems, alarms, controls, panels and sub panels, is far more expensive to construct than a simple stick framed house. The Code becomes stronger as the risk and complexity increase.

That means, that at writing in 2022, a guide on how much it costs to build a single unit of housing at the density of a single family home is ~$250/Sq.Ft. All the way up to about 4 units, that would be about roughly the same. As you add on stories/units, it increases. A 10 story building, with concrete, elevators, fire suppression, etc. could easily increase to $300/Sq. Ft. or more. By the time you get to high rises proper, construction costs can easily surpass $650/Sq. Ft. - which is often why "Towers" are always "Luxury Towers". At $650/Sq.Ft. a 1000 Sq. Ft. One Bedroom Condo base cost, without profit, parking, land, insurance, any shared amenities (like a pool, gym, etc.) is $650,000 - meaning its going to have to sell well in excess of $1million for one bedroom (as it is in central towers in bigger cities all over Western Canada).

This is not developer greed, this is the minimum cost of building a unit in a high tower, meeting building code, and making it safe. Towers are expensive, that's just the way it is, even without a building code.

Many aspects of Building Code are not strictly about safety. Minimum plug points in a room for example might provide comfort and convenience, but do not actually make you any safer (though a small argument could be made that the added electrical complexity might in fact make you slightly less safe). Others are not so clear.

Stairways for example are extremely contentious. Stair code is different for different uses in our province, suggesting that there is not one stair which is most safe. Recently, the minimum width of the stairs in Commercial increased from 36" to 40" regardless of use or occupant load. Whether they access a space for 40 people or 4 people, that extra 4" adds 6-7 Sq. Ft. of extra stairway, and at $300/Sq.Ft. that change has added ~$2100 for each stair to the cost of the building. Have people being dying or injured all over the province because the stairs were not 4" wider?

One province over in Alberta, the stairs are allowed to be built steeper than they are here, so too are spiral stairways allowed, which they are not in BC. In Europe, Asia, South America, Africa and old Cities like New York and Montreal staircases are far less regulated, if not at all. Thousands of hotels, tourist attractions, and city streets in Europe are filled with stairs, thousands of stairs, that would be illegal anywhere in BC.

|

| stairs in Italy. these would not pass any North American code, yet have transported these residents for thousands of years. |

Per capita incidences of injuries or deaths on stairways are a wash. There does not appear to be any real world data outside of controlled lab experiments that correlates Europe, New York or Montreal having more stair related injuries or deaths than BC or Canada generally. In fact, North America has slightly higher rates of stair incidences than Europe, despite the amount of stairs, the use of stairs, and the inconsistency of stairs all being many factors higher in Europe than Canada. Speculating on this is outside the scope of this article, but maybe just Google "

Risk Homeostasis Theory".

Double Decker buses in the UK have spiral, narrow, steep stairs - on a moving vehicle. They also have wheelchair ramps and step free access and service superior to any North American bus system. For someone in a wheelchair unable to drive, this system offers them independence and safety far superior to any North American system, within the existing transit network.

Other aspects of building code, like insulation requirements and other climate change/pollution control initiatives increase costs of building, in some cases quite dramatically, but in theory will benefit society in the long run. I would remark, that often these requirements increase with density, as the big developers are more able to pay for these items, and they make up a smaller part of the budget as a whole, the larger the project gets. So its more politically opportunistic to put the cost on a big development than a small one.

I would argue though that an apartment dweller, whose unit is insulated on all but one or two sides by another apartment, and lives in an area which generates fewer and shorter vehicle trips, is already leaps and bounds ahead of a single family home - bleeding heat on 5 sides, generating more and longer car trips. If Green is your concern, the code requirement should be higher for low density housing, not the other way around. In all cases though, these requirements factually drive up the cost of building housing (not necessarily operating or living in housing).

Perhaps continuing on to read Steve Mouzons "The Original Green" might help to continue the complicated nature of politics led building code changes.

Interestingly, the building code minimum for housing standards are so high, that what is behind the wall, and under the floor; most of the costs of construction - between the lowest end affordable housing projects and the highest end luxury units - are negligible. All but the highest end luxury may have fancier fixtures, fancier lights, higher ceilings, and a better view - but intrinsically all new buildings are built to just about the same standard. This is why "all new housing is luxury", is because it is.

We no longer allow people to build their own house from a Sears kit, with some folks from the church coming by on Saturday to hand mix the concrete and pour the foundation. Sweat Equity is now mostly illegal. The complexity of the Code is so high that on simple construction projects there often needs to be a team of engineers, architects, code consultants and lawyers nearly as large as the team who actually constructs the project. The time to get a permit is often comparable to the time to actually build the project - and there is certainly hundreds of noteworthy cases just in our province of the permits taking far longer than the actually construction.

|

| unpermitted, often user built, kit house - thousands of them still stand today when newer code built properties do not and are demolished or falling apart |

If we want to find ways to make housing more affordable, there is thousands of small changes in building code, that would not affect the safety of the building that one could pursue. All the way from the requirements of the permitting process, to the complexity of modern HVAC systems (themselves regulated by CSA etc.).

If I were going to pursue this, the very first thing I would do is examine all the places that our own BC Building Code conflicts itself and analyze how important that item could truly be if it is self-conflicting. Then I would compare it to Alberta's Code and start asking the same questions. Then go out to Washington States Code. And outwards eventually to European ones.

If there is no clear answer as to why the height of a door knob can be different in all 11 different constituencies, perhaps there is no perfect height for a door knob, and perhaps it doesn't matter all that much. Or does it really matter if a barrier under a railing is oriented horizontally, vertically, with wide spacing, narrow spacing, or at all - as many places have no railing requirements at all. Perhaps a "best practices" or results based code is preferable in many instances. In the world of mass production, rarely is the end installer or designer even making a choice other than searching for an existing product that meet local code - eliminating the benefits of product comparison based on the actual intrinsic values of the product itself. Meaning - I as a developer am sometimes forced to buy an inferior product at a much higher price because the local code doesn't allow for some slight variance in a nail pattern, or its missing a sticker. This happens alot in plumbing particularly in my experience.

|

this Cotswold village did not find the need for railings against the river, and the pub used planters for the patio. In Kamloops the patio requirements code is 17 pages long, and for years was contrary to the provincial standards for liquor licensing, requiring a person to change the height of the railing depending on which inspector was inspecting

| | as can be seen on this Hackney patio, the drinks, and the surface on which its sits (the uneven cobblestone road) with a lack of societal collapse, perhaps indicate that we may have overthought this |

|

All that would lead up to slimming the code book, saving the time and effort of the plan checkers, and the plan makers - allowing more of our collective resources and time to be directed towards actually building housing rather than regulating what is primarily standardized materials in the first place.

Building Code reform may only save $20/Sq. Ft. in hard costs, the primary savings are in time. There is absolutely no silver bullet in Building Code reform the way there is in zoning. The curve of the graphs on their own represent that.

The most significant change here would be to allow repurposing of older buildings that don't meet todays code, but did meet code maybe 50 years ago. Sometimes the building technology of the day they were built 100 years ago is no longer accounted for in todays code, despite being perfectly safe. Most of the time, the brick building, and its stairs, cannot structurally be moved, but the existing stair, sometimes only 10 years old, doesn't fit new code. Same with bathrooms. This is why so many fantastic heritage buildings get torn down or sit boarded up and rotting.

There is significant savings in keeping the bones and structure of older buildings. If you already have the walls, roof and foundation, renovation costs could be < $50-$100 per Sq.Ft. - but if you have to first demolish everything to bring it up to modern code, you actually spend even more than if you had a no building at all. There needs to be room for compromise and results based solutions and improvements.

Prioritizing repurposing of older building through regulatory relief on things that are not structural, electrical or plumbing with imminent health and safety concerns could dramatically lower the floor of many housing prices. Old buildings which already have a bunch of their structure paid for is a great way to bring more housing to market, faster, and preserving heritage buildings that sit underutilized and threatened (looking at you Stuart Wood, Old Courthouse).

PARKING / SHARED AMENITIY / LANDSCAPING COSTS

Lastly, related to and regulated by Zoning, but separate from density - are the periphery things that are not directly part of the actual housing unit for sale. They also cost money and have regulated minimum requirements, and end up split by the units for sale. These things include Parking, Shared Amenities and Landscaping Costs.

Zoning will say for example that a development has to have 5% of the land area be landscaped, or 5% of the projects budget be devoted to the same - designed by a landscape architect (one more consultant). Those costs are then divided amongst the units that are for sale. So if a 20 unit project has to spend $300,000 on landscaping, that cost would be divided by 20, adding $15,000 to each unit. Not saying landscaping is bad (though I would agree with this

author in Victoria that in many cases it is).

Shared Amenities are not formalized in the code as prescriptively as landscaping, they are usually more of a negotiation with planners. Something like a rooftop balcony for occupants of a apartment building would be part of this. If that costs another $300,000 for 20 units, it is again, another $15,000 to each unit. The more complex and fancy the amenity, like a pool, the more expensive per unit. While these are not usually regulated to a minimum standard, they do cost money, and projects have been known to be held up by this. Often this is a misunderstanding between the tradeoffs of urban vs. suburban life. What you trade for the backyard in a suburban home is the amenities of an urban neighbourhood - a communal rooftop balcony or shared gym in the building is often not part of that tradeoff for the vast majority of people, examined

extensively in

Chapter 7. Meaning, apartment dwellers rarely pick one building over another because it has a gym or sauna for residents use. In addition, these amenities are rarely well used, as they are neither private space where you can use as you like, nor are they public space, free for anyone to use. As well, strata's and renters associations typically defund them almost immediately as the maintenance concerns and costs surrounding them are not worth the effort.

A fairly priced neighbouhood gym is usually preferred to a poorly equipped and poorly maintained strata owned one. Same for a public park down the block vs. a strange greenspace in the zoning setback.

|

| you can see on the rooftop of the Station on Tranquille - the plants are dead, and there is no furniture, the strata decided specifically not to have something here as it was going to be a maintenance concern that they did not want to have to take care of. |

The real doozy though is Parking Requirements.

If the parking has to be provided at surface level for the units (like 2 stalls per townhouse, or 1.5 stalls per 2 bedroom condo) - then you have to account for the cost of the land that could otherwise have been more housing, more landscaping, or other. One parking stall typically needs about 400 Sq. Ft. at grade to account for aisle widths, turn arounds, ramps, etc. If the land costs $120/Sq. Ft. to purchase (a standard 50x100 lot at $600k) - the minimum land cost for one parking stall is $48,000.

This is an opportunity cost. This is what you are 'spending' on the stall by forgoing what else that land could be, like more housing, yard, etc. There is a construction cost associated with a parking area as well - the asphalt, storm sewers, extra landscaping, curbs, line painting, add about $30/Sq. Ft. more. So at a value of $150/Sq. Ft. that Parking stall is closer to $60,000.

If the land cost per unit was $120,000 - the $60,000 is already paid in that. However if you doubled the number of units or had half the land, as you did not have to build all that parking, the land cost per unit would now be $60,000. You could look at the parking requirements as driving up the land cost, or a foregone opportunity, but you still have to pay. You may as the developer still choose to build the parking, however this article is about the Floor of Housing Prices, the cheapest one could possibly build to provide affordability. Do people want parking, of course they do, but by forcing people to pay for it regardless, is making housing substantially more expensive.

Even worse is "going underground". While there is no opportunity cost on the land in this case (other than possible basement uses), the cost of ramps, suspended slabs, flood pumps, sloped flooring, massive ventilation systems, A/C, heating, fire suppression, etc. put structured parking around $250/Sq. Ft.+ just like the rest of the building. These stalls need more than just 400 per Sq. Ft. as the ramps cannot be used for parking , but are required to access the stalls. Parking isn't much good if you can't get it it. So too the stairwells and elevators take up space, and cost money to build, to access the parking - so 600 Sq.Ft. per stall is probably more appropriate, though on small projects this number will be higher, and on larger projects lower. At that rate one structured parking stall is $150,000 in hard construction costs.

A 350 Sq. Ft. micro suite with a construction cost as low as $90,000 - the mandatory parking stall the code requires providing has more square feet and sometimes costs more than the living unit itself. If we are serious about providing a place to live, forcing them to provide more square feet and more money to parking is not helping.

A special note on parking - just because it is required to be there, does not mean it actually fits on a development site. Just like stairs and bathrooms in renovations. This is explored more vigorously in this

case study. Required Parking can quickly kill any potential project regardless of the economics. Geometry beats economics every time.

A excerpt from Donald Should on the subject:

SUMMARY SO FAR

With building code requirements, we make renovations nearly as, if not more expensive than new housing. When buying land, we make sure its the most expensive way - 1 or 2 units max, unless its tall and downtown, in which case we make sure the construction costs are high. And only provided we can provide the minimum amount of parking regardless of transit of if someone looking for housing they can afford can afford a car. Or even wants a car.

How do we fix this?

The Missing Middle. We have to split the cost of the land to lower the land costs, but build at a height and density that keeps construction costs low. And we have to mitigate the requirements for shared amenities like parking and landscaping that drive costs up. It does not mean that we shouldn't provide them where people are willing to pay for them - it is that we should not make them a requirement to build anything at all. Should we require all buildings to have pools? Probably not. We need to apply that logic to any required shared amenity if we are serious about affordability. And if we are worried about our amenities, its best left to our civic institutions to provide, not strata's, home owner associations and corporate landlords.

This is why "The Missing Middle" is how we address Housing Affordability with new homes. And we did this up until the government started heavily regulating the housing industry in the 80s, as you can see by this aerial view of the North Shore. There was all sorts of buildings, for all sorts of people, all up and down this graph. Apartments, duplexes, four plex's, suites, etc.

This is also a contributing factor to why Europe, which has had an unregulated market in this sense for thousands of years (until relatively recently), nearly always hit an equilibrium around 4-8 stories depending on the City. They have very little low density, and very little high density, because the medium density neighbourhood scale is most effective at delivering the best economic and affordable outcomes. Interestingly it also seems to be best at achieving the best mobility standards as well.

|

Paris - nearly all medium density

| | Leon Kriers illustration on city form |

|

Right now though, we regulate nearly the entire City to a unit count of 1 per lot, and even regulate the minimum size of that lot. Or we allow for high density construction on a very limited number of lots (which are also the most expensive in the City, partly because they are the only ones big developers can bid on for big projects).

The way that our zoning and building code interact ensure that the only housing we allow to be built is the most expensive from a land cost perspective, and also the most expensive from a building cost point of view - and then we toss on a bunch of shared amenity costs like Parking Requirements for good measure.

Does Kamloops ever want to see a new family sized dwelling on the market for under $500,000 ever again? It is only through adjusting the minimum rules on what we consider to be a house that we are going to change that. This is not about preferences. Many people would prefer all sorts of housing options - myself an apartment in a walkable area - and other people on an acreage. This is about the straight facts of what it takes to get the closest to affordability in Urban areas.

Comments

Post a Comment